History

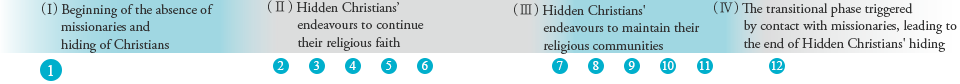

(Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

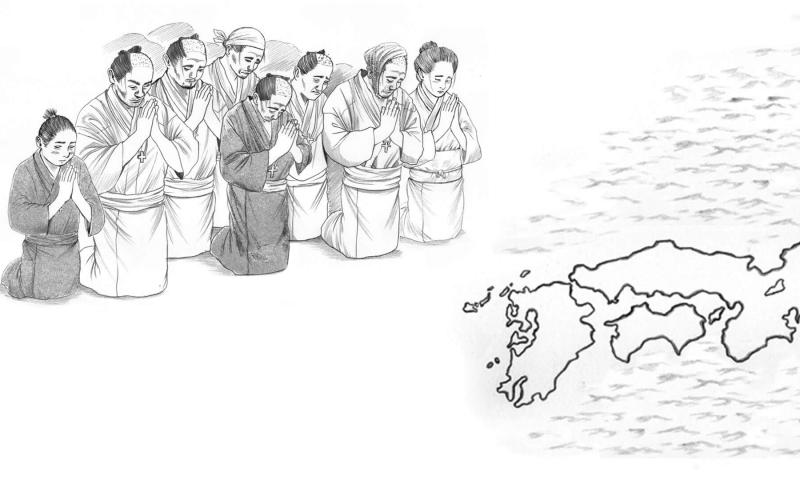

Hidden Christians’ tradition to maintain their faith

(Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

(Ⅱ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to continue their religious faith

(Ⅲ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to maintain their religious communities

(Ⅳ) The transitional phase triggered by contact with missionaries, leading to the end of Hidden Christians' hiding

(Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

(Ⅱ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to continue their religious faith

(Ⅲ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to maintain their religious communities

(Ⅳ) The transitional phase triggered by contact with missionaries, leading to the end of Hidden Christians' hiding

The introduction and spread of Catholicism

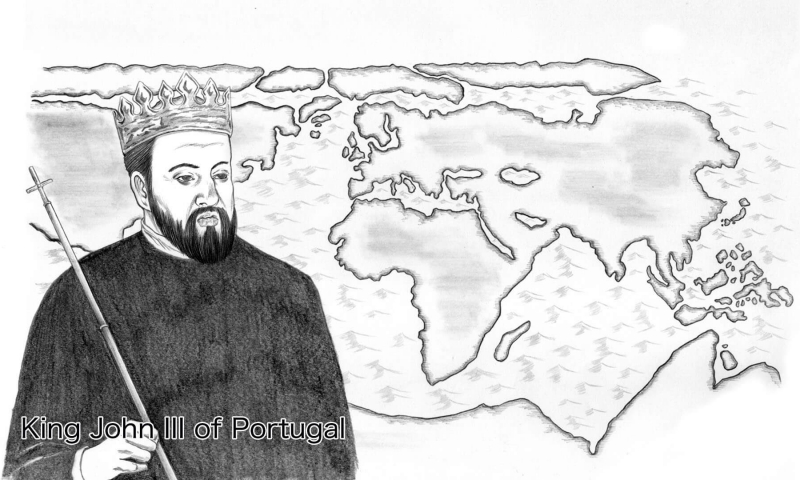

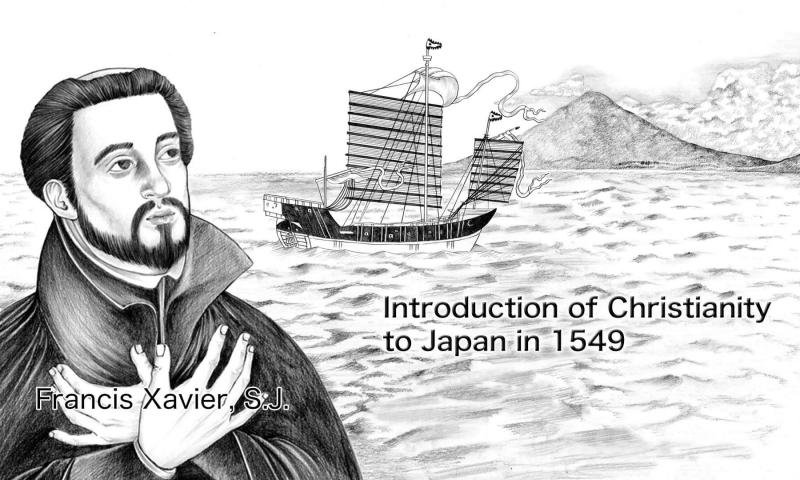

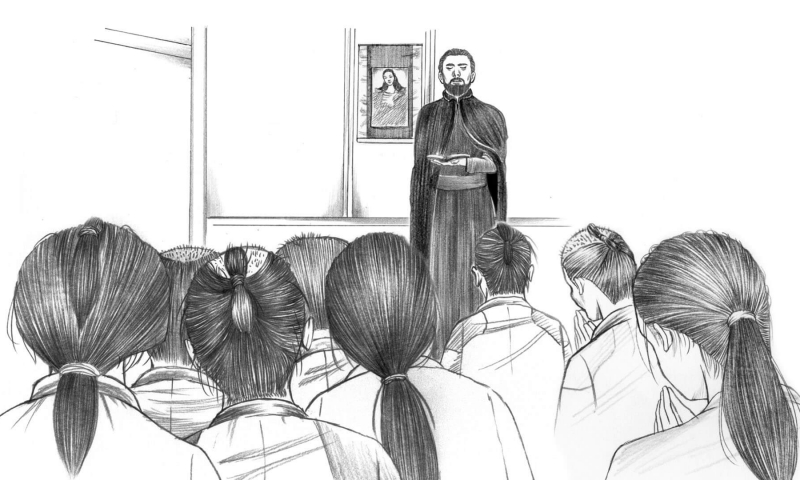

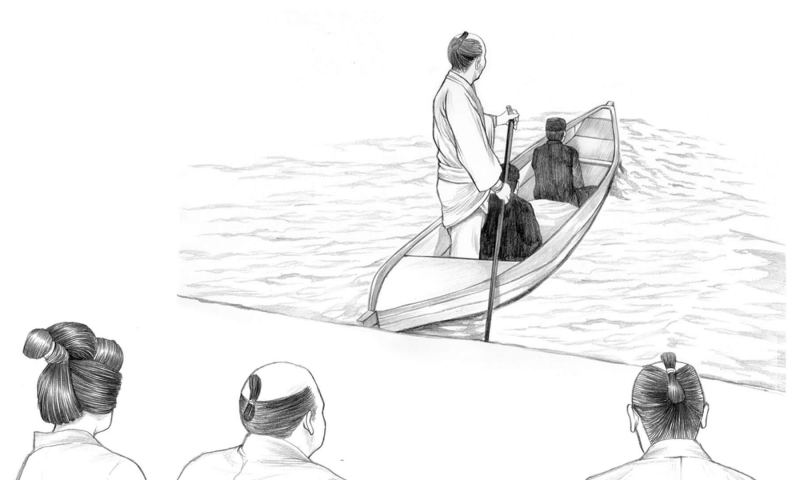

Portugal’s global expansion that began in the mid-15th century had reached Asia by the end of the 15th century. At the request of the Portuguese king, Jesuit missionaries actively expanded their activities from their base in India. In 1549, the Jesuit priest Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima on a Chinese vessel and introduced Catholicism into Japan. Consequently, other missionaries soon followed Xavier’s lead, arriving in Japan to further the spread of Catholicism.

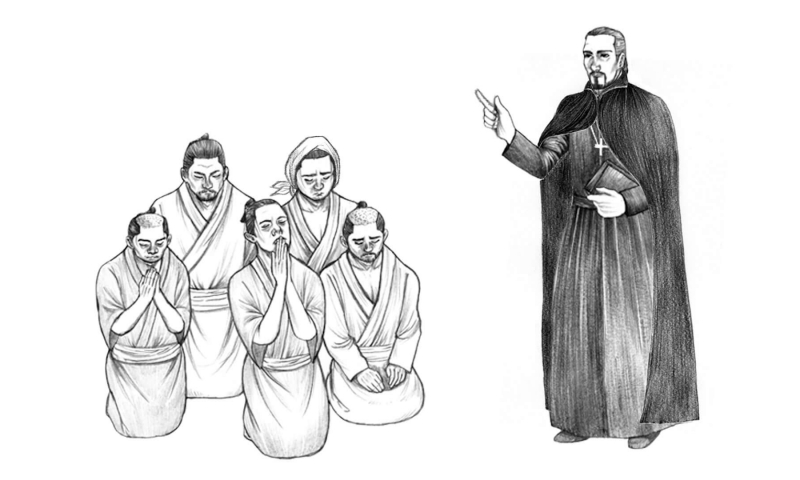

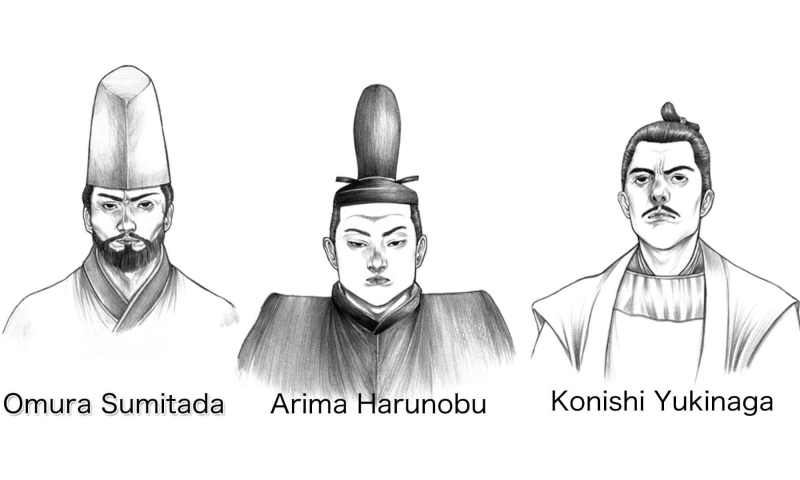

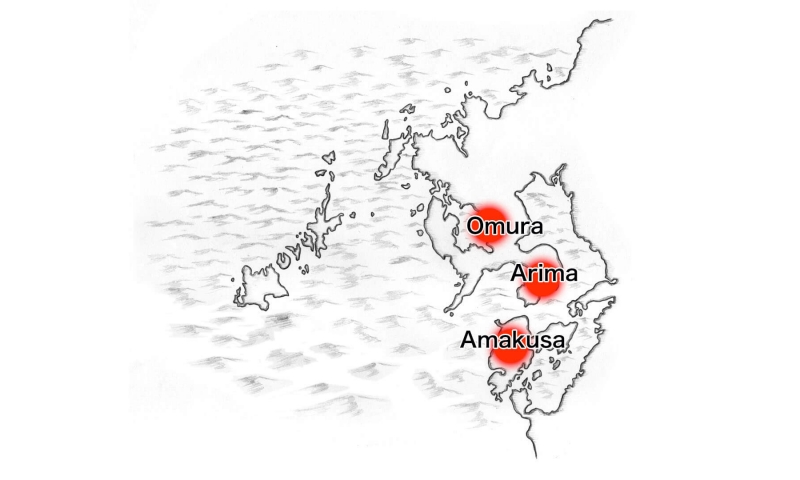

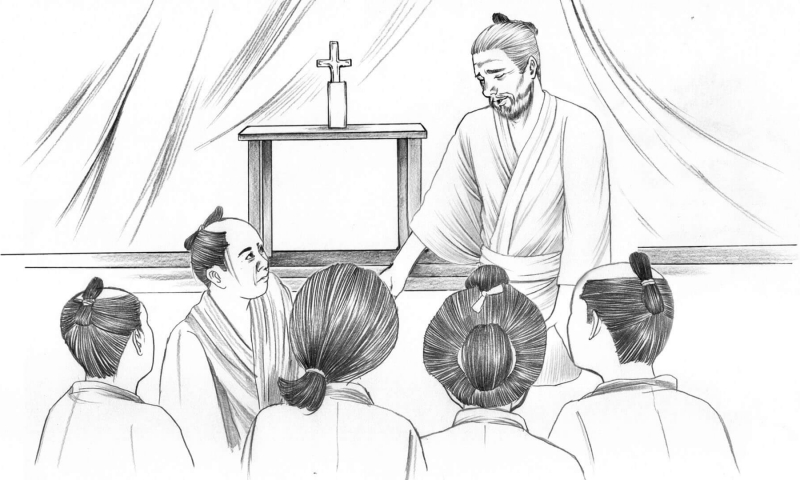

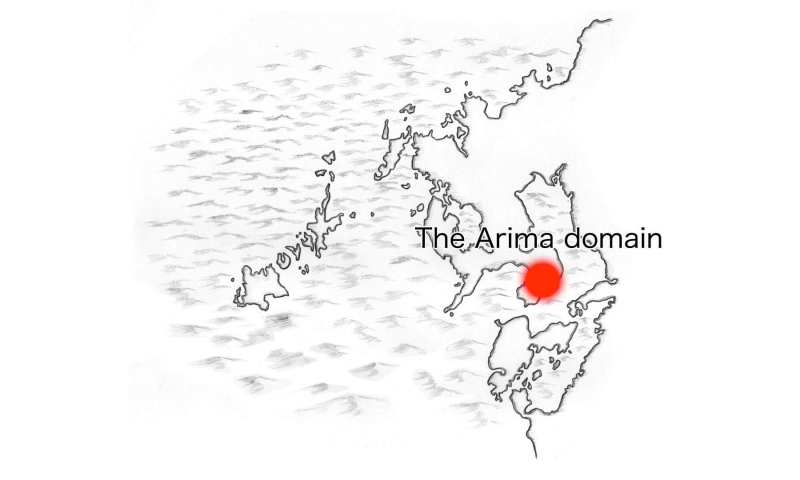

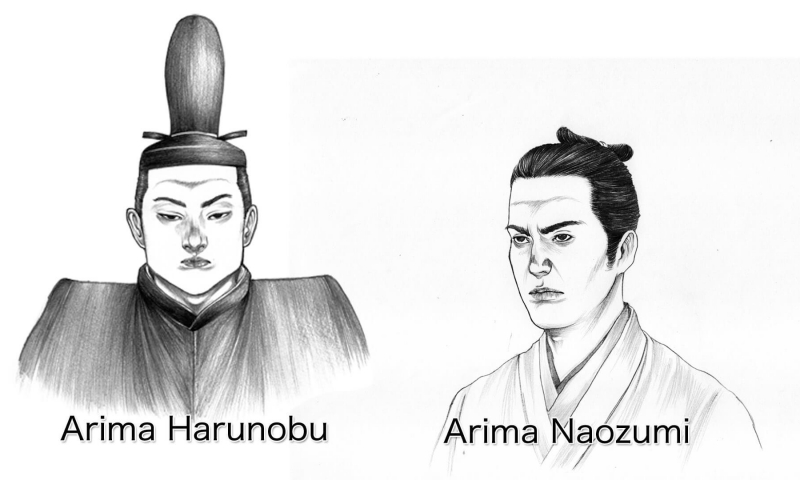

The missionaries first approached the feudal lords (daimyo), converting them from Buddhism to Catholicism, and then converted their retainers and the local people in their domains. When the feudal lords did not accept Catholicism, the missionaries offered them gifts and used their good offices for trade in order to obtain permission from the feudal lords to spread Catholicism among their retainers and the common people. Using this strategy, they gained many converts in a short period. Many of the feudal lords in the Kyushu area who sought to benefit from trade with the Portuguese ships (the so-called Nanban trade) therefore accepted the Catholic mission in their domains. Some of these daimyo converted to Catholicism and became devout Catholics. They were called Kirishitan Daimyo, and they provided protection to the Christians in their domain and supported the missionaries, allowing them to spread the Catholic faith. Omura Sumitada, Arima Harunobu, who later built Hara Castle, as well as Otomo Sorin were all well-known Kirishitan Daimyo on Kyushu Island. Konishi Yukinaga, who took control of the Amakusa domain in 1588, was another.

The missionaries expanded their missionary work from Kyushu Island to the neighbouring Yamaguchi region, and then moved further eastward into the Kinai region. They established faith organisations so that the Japanese Catholics were able to maintain their Christian teachings by themselves. These faith organisations, known as Kumi, were established in the Arima, Omura, and Amakusa domains of the Kirishitan Daimyo, playing a leading role in spreading and strengthening Catholicism, as well as maintaining the faith during the phase when Catholicism was being introduced into Japan, at which time the number of European missionaries was still relatively small. These faith organisations took root more firmly in the villages within the areas where the missionaries were active and prepared the ground for Hidden Christians to maintain their faith later on during the long period when there was no guidance by missionaries or Japanese priests.

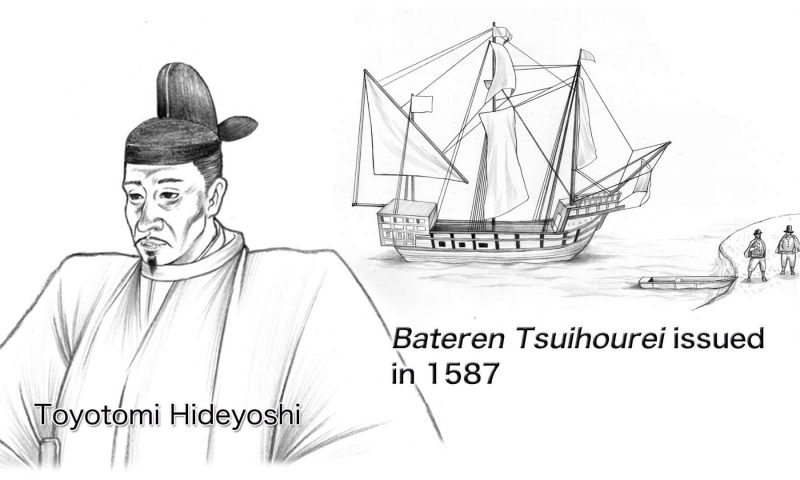

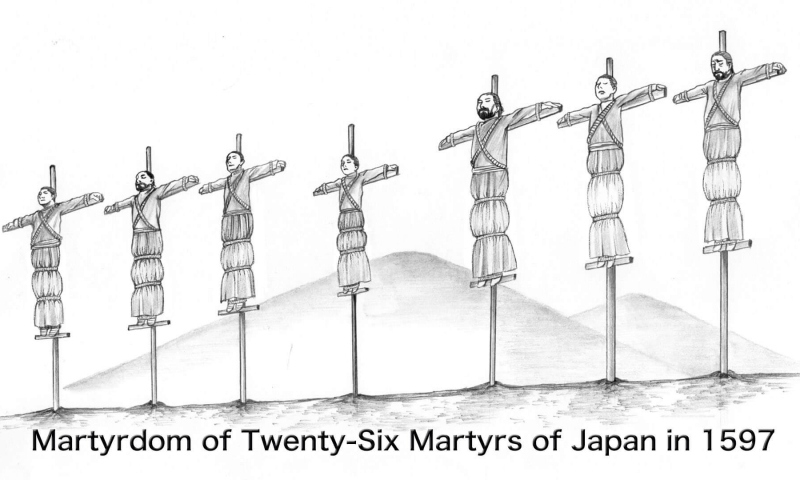

While missionary work was progressing, centred on Kyushu Island, the Yamaguchi region and the Kinai region, in 1587 Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became the supreme ruler of Japan during the age of provincial wars, issued an order to expel all Catholic missionaries (known as Bateren Tsuihourei) in Hakata (present Fukuoka), taking control of Nagasaki, which had been donated to the Jesuit order, and putting it under his direct control. While Hideyoshi issued a policy forbidding missionary work in Japan, he did not stop it completely but promoted continued trade with European countries (the Nanban trade), aiming to profit greatly from it. Therefore, his anti-Catholic policy was not strictly enforced. However, in 1596, an incident known as the San Felipe Incident occurred, giving rise to reports that the missionaries were allies of Spain and were actively helping to expand its territory. Hearing these reports, Hideyoshi became enraged and had 26 Christians, including 6 Franciscan monks who lived in the Kinai region (around Kyoto), rounded up and executed in Nagasaki in 1597 (the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Japan).

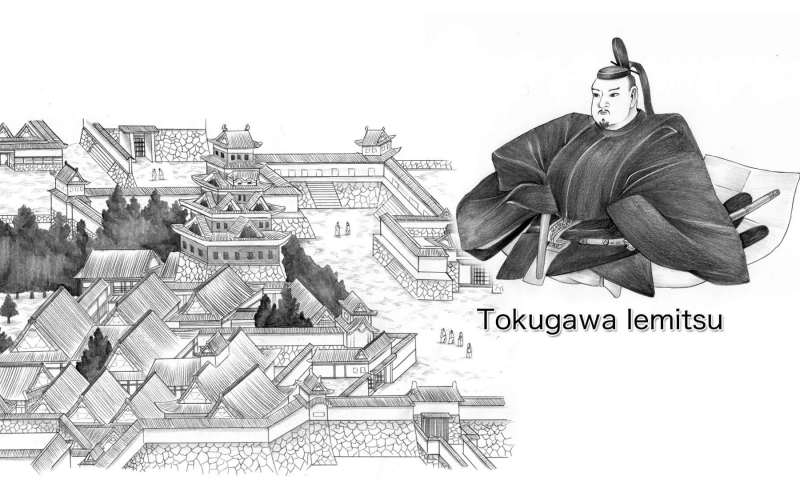

After Hideyoshi’s death, Dominican and Augustinian missionaries arrived in Japan and competition between the religious orders intensified in order to gain more converts. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who ruled Japan after Hideyoshi and established the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603, prioritised continued trade with Portugal and Spain for a while, and left the Catholic missionaries free to convert more Japanese people to Christianity. Thus, the number of adherents to Catholicism kept increasing, rising to a peak of more than 370,000 in the early 17th century.

Full enforcement of the ban and concealment of the Catholic faith

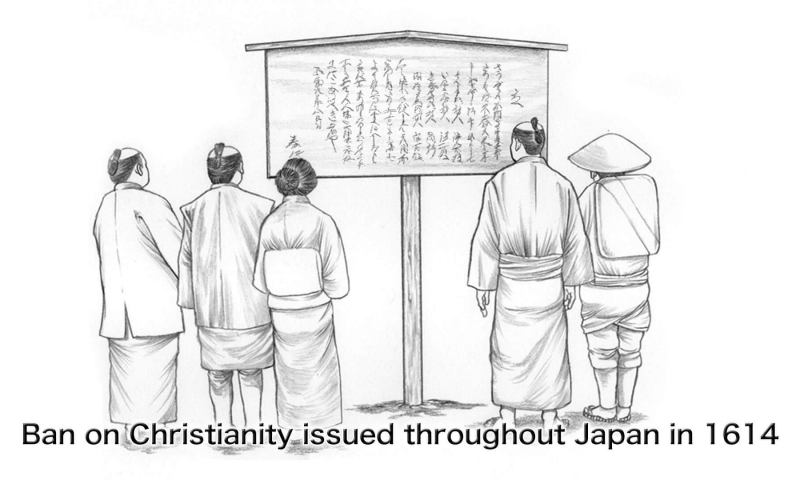

In 1614, the Tokugawa Shogunate was preparing for war against the Toyotomi clan of Osaka in order to cement its supremacy over Japan and it issued a nationwide ban on Christianity to eliminate any further power games within the Shogunate and to solidify the feudal system centred on the Tokugawa clan. Missionaries were expelled to Macao and Manila and church buildings were demolished. However, missionaries tried to stay in hiding in Japan, or to surreptitiously reenter the country in order to keep providing guidance to Japanese Catholics.

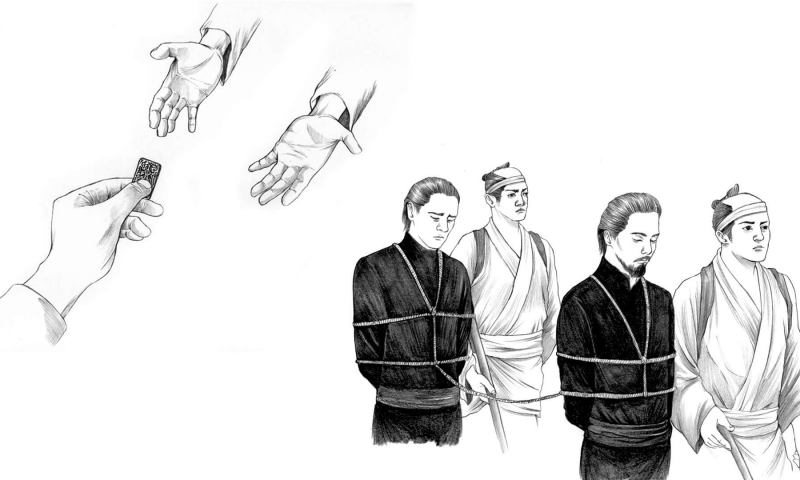

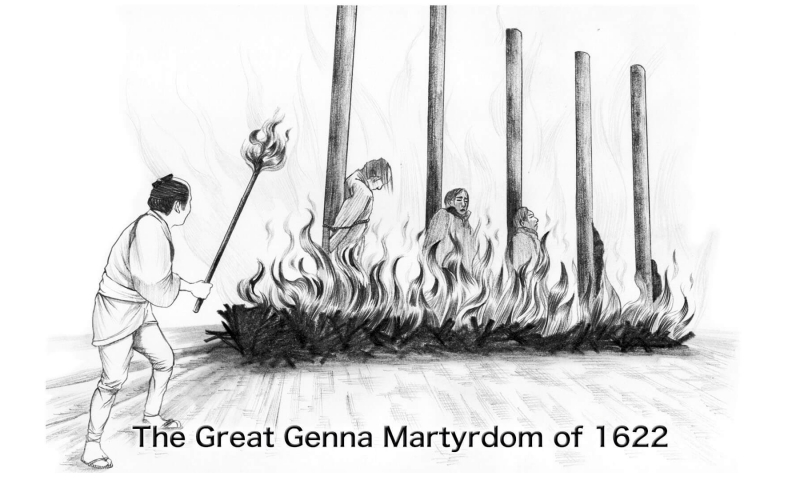

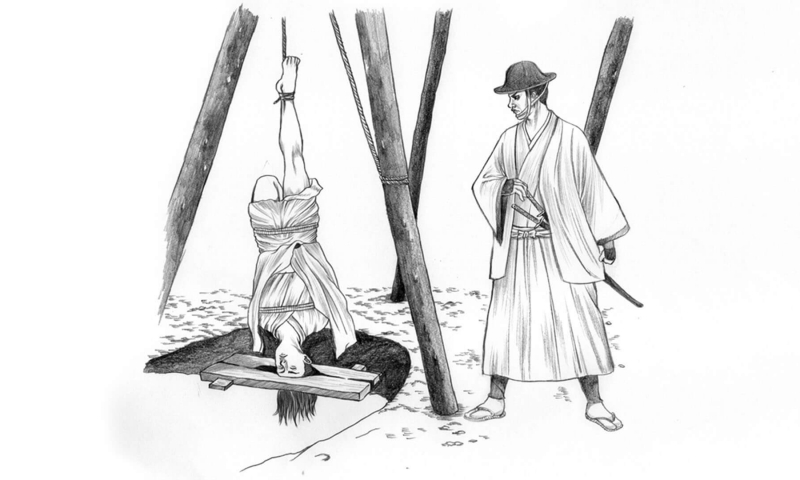

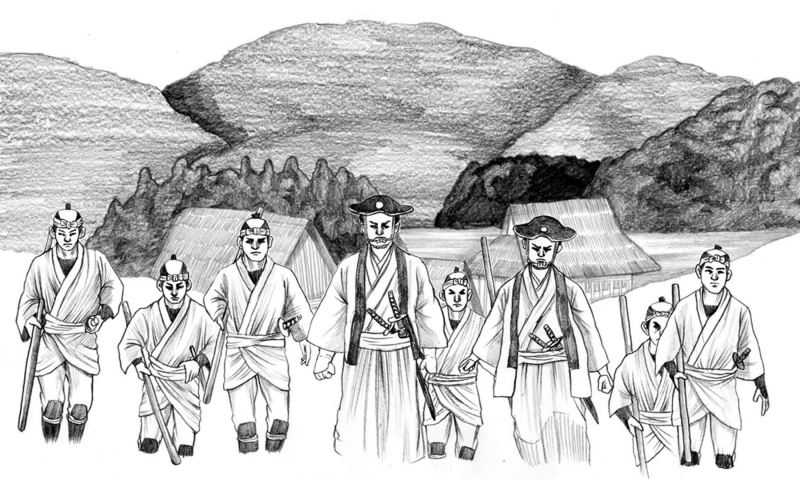

For that reason, the Shogunate offered a reward to all those who could provide information leading to the capture of any underground missionaries, and when caught, the missionaries and those who had helped hide them were tortured and sentenced to death. In 1622, a total of 55 Catholics who had been incarcerated in Nagasaki, including priests, monks, and the Japanese who had hidden them, were burned and beheaded (the Great Genna Martyrdom).

At first, common people were left alone, but the Shogunate gradually intensified and expanded the scope of their investigations. Those who were found to be Christians were subjected to severe torture and forced to renounce their faith. In the city of Nagasaki, which had previously been the centre of missionary work and where most of the residents were Catholics, religious beliefs were not initially subject to regulation, with some exceptions. However, Mizuno Morinobu, who was appointed as magistrate of Nagasaki in 1626, and Takenaka Unemenosho, who succeeded to the post in 1629, strictly enforced the ban among the common people with brutal torture, compelling almost all of them to either renounce their religion or accept martyrdom.

Following the imposition of the ban on Christianity by the Shogunate, the members of the ruling daimyo class and the samurai who had once enthusiastically accepted Catholicism were the first to renounce Christianity, followed by the common people. Meanwhile, in the areas surrounding Nagasaki, the former base for missionary work, and in villages where Christianity had once flourished, the faith organisations were maintained in secret at the commoner level.

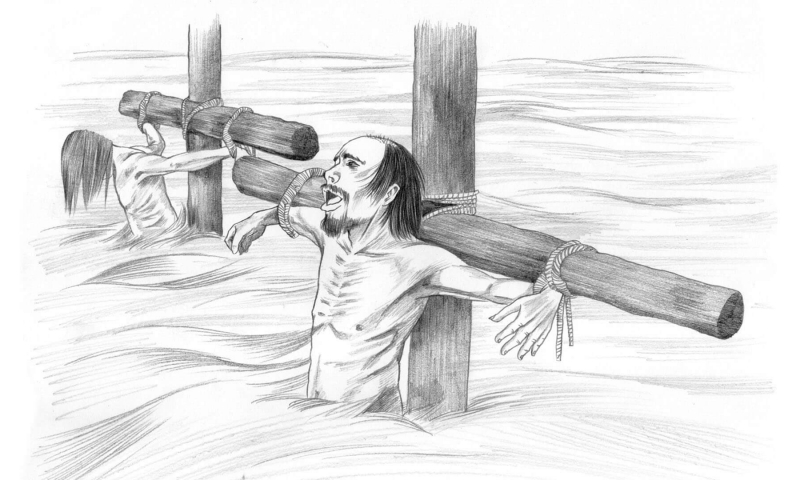

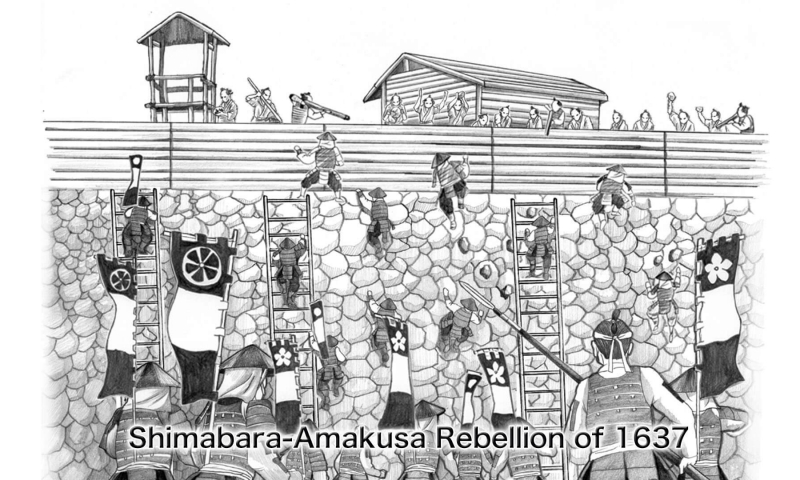

Establishment of the national seclusion policy, the destruction of faith organisations, and their continuation in the Nagasaki region

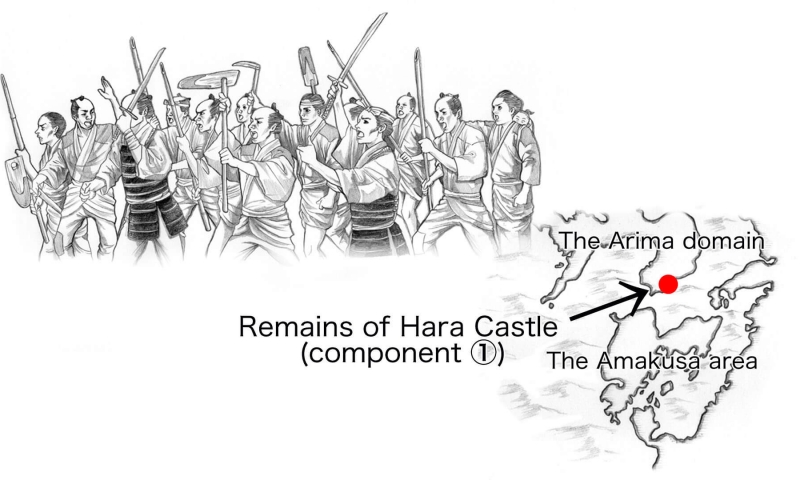

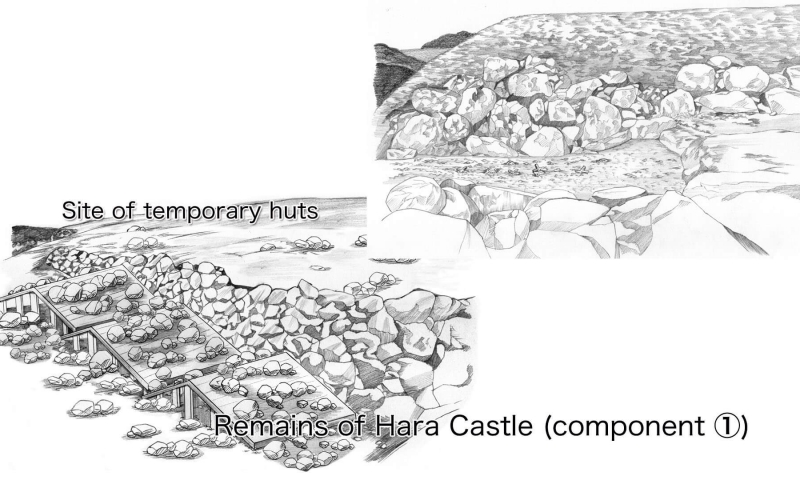

In 1637, despite the imposition of a strict ban on Christianity throughout the country, the starving people of the Arima domain and the Amakusa domain rebelled against the tyranny of their feudal lord. This uprising is known as the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion. In the Arima domain, located in the southern part of the Shimabara region where Christianity had once flourished, the Kirishitan Daimyo Arima Harunobu was banished over a bribery case and later sentenced to death. When his heir, Arima Naozumi, was forced to transfer his land to the Hyuga domain, many of the Catholic samurai abandoned their rank to stay in the Arima domain and continued the religious faith alongside the local Christian population. Their uprising was then joined by more than 20,000 peasants from the Shimabara and Amakusa regions, all of whom had secretly continued their Catholic faith. They were led by the former vassals of the Arima clan and another Kirishitan Daimyo, Konishi Yukinaga, who had once ruled Amakusa, and were besieged in the abandoned castle of Hara (Remains of Hara Castle). After four months of battle, the uprising was suppressed with the Shogunate forces killing almost all of the rebels. Hara Castle was then utterly destroyed by the Shogunate so that it could not be used for another rebellion.

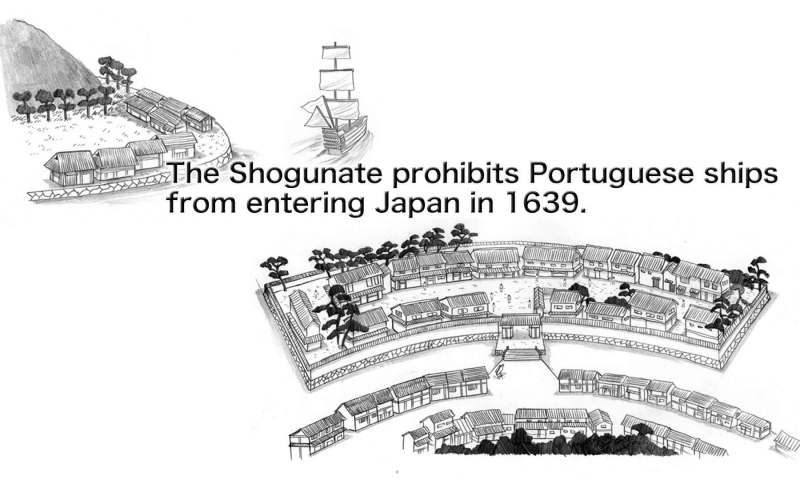

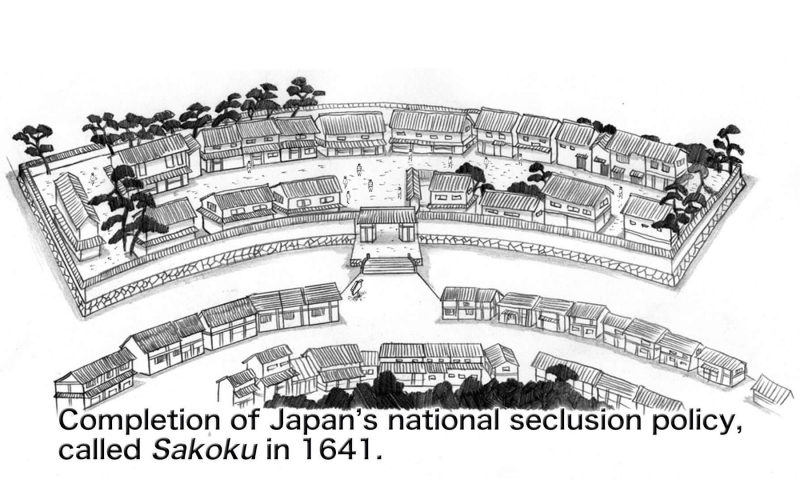

As a result of the rebellion, the Shogunate regarded Christianity as a major threat to its rule over Japan. In 1639, it prohibited all visits by Portuguese ships that could possibly be used to smuggle missionaries into Japan, and completely cut off its trade relations with Portugal that had lasted for nearly a century. This was the beginning of Japan’s national seclusion policy, called Sakoku. Under this policy, trade with Europe was limited to the Dutch, who were Protestant rather than Catholic, and the authorised entry port was moved from Hirado to a manmade island created in Nagasaki, known as Dejima.

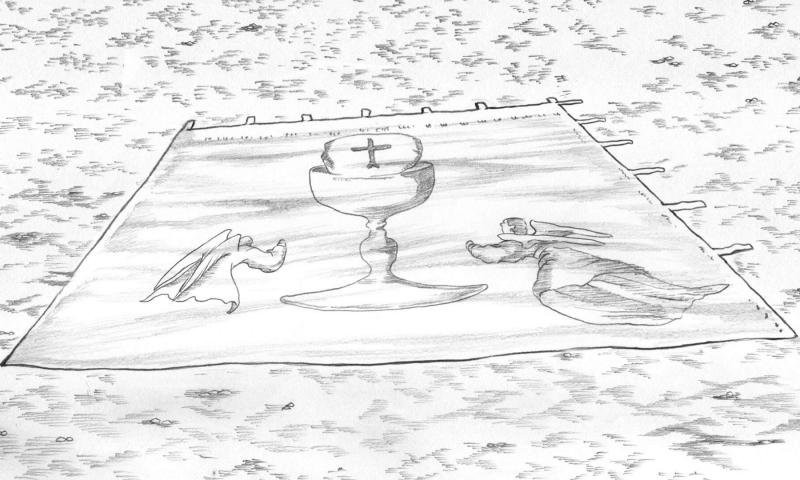

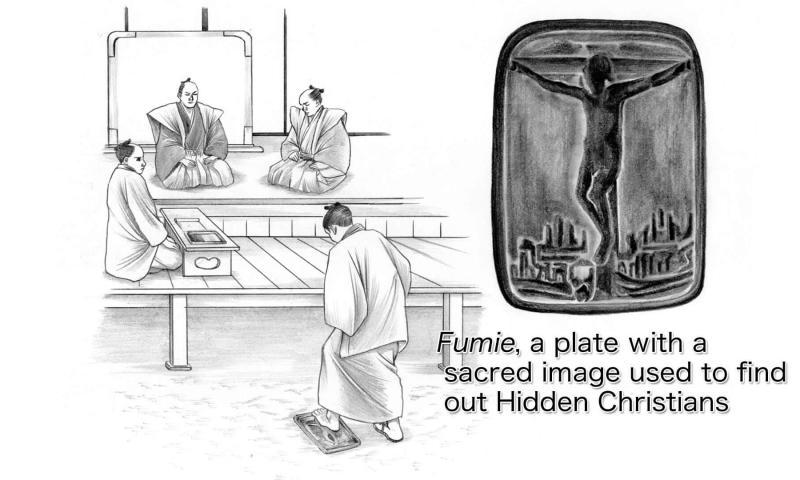

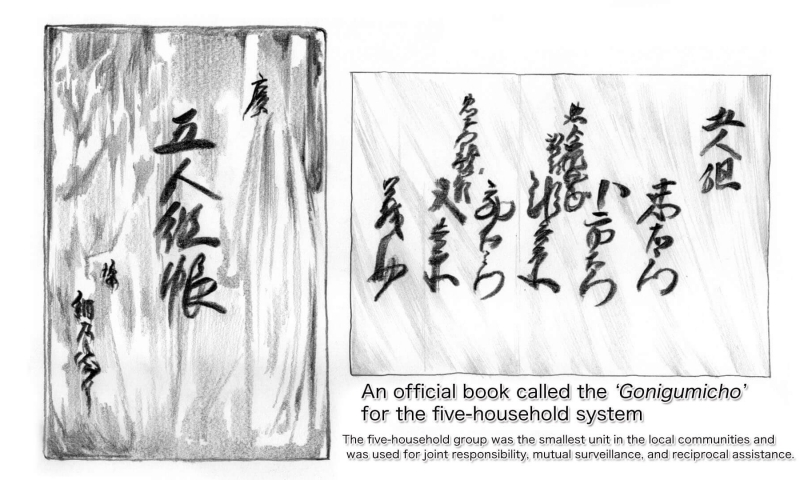

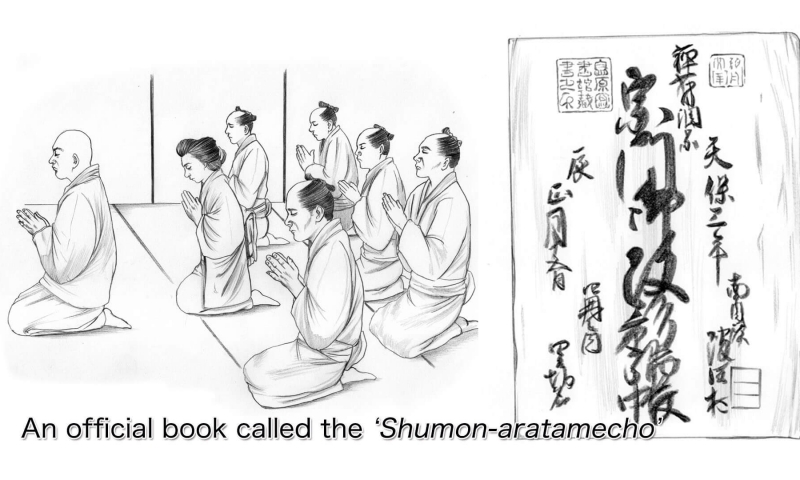

As the search for Hidden Christians intensified under the ban on Christianity, the Shogunate introduced the Efumi ceremony, forcing people to step on sacred images, medallions or other Christian devotional items. The focus of their intelligence-gathering efforts was expanded and the ‘five-household group’ (Goningumi) system was introduced to uncover Hidden Christians. Everyone was required to belong to a Buddhist temple and have his/her religious background and affiliated temple registered in an official book called the ‘Shumonaratamecho’, which was placed under the control of the temple (the Terauke policy). As a result, a total of 75 missionaries were executed and more than 1,000 Japanese Catholics were martyred from 1617 to 1644.

In 1642 and 1643, ten missionaries split into two groups and tried to steal into Japan but they were all captured. The Shogunate’s expulsion of missionaries made steady progress, and the last missionary, Konishi Mancio, was eventually martyred in 1644. There was no further missionary activity in Japan after this point and the remaining Hidden Christians had no other choice but to go into hiding and find ways out to maintain their faith by themselves for the following two and a half centuries.

Even in the midst of this period of intense investigation and oppression, there were still some Catholic populations throughout Japan that chose to live in hiding and that remained undetected up until the mid-17th century. Evidence of this can be seen in a series of large-scale crackdowns (Kuzure) on Hidden Christians recorded in the latter half of the 17th century called Kori Kuzure, Bungo Kuzure, and Nobi Kuzure. While Hidden Christians vanished from many parts of the country, there was one region where the faith organisations run by Hidden Christians continued to exist even in the early 18th century. This was the Nagasaki region, the former base for missionary work where long-term guidance by missionaries had enabled each village to form a strong faith organisation to maintain their religious beliefs.

Component of this stage

> (Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

> (Ⅱ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to continue their religious faith

> (Ⅲ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to maintain their religious communities