Component

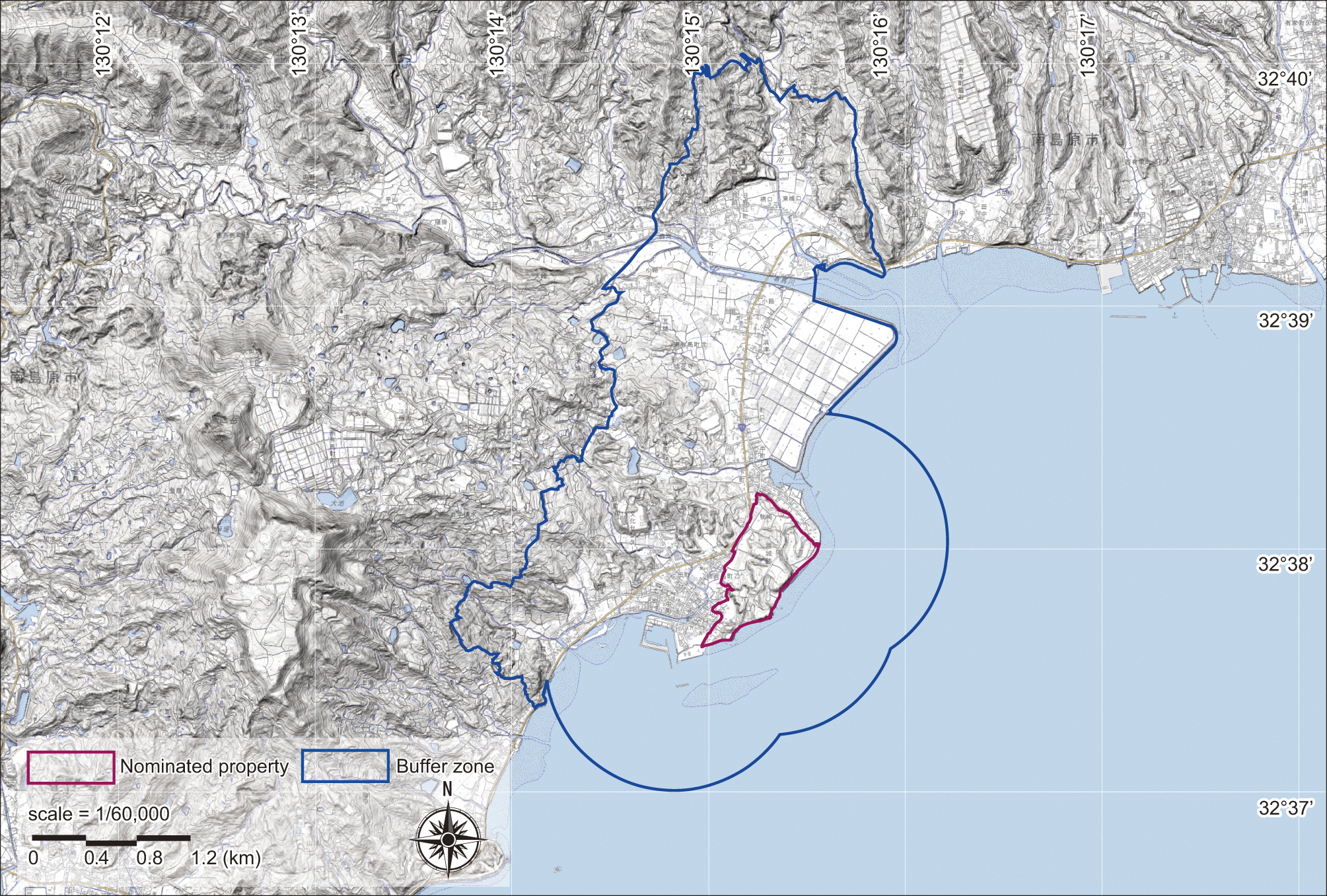

Remains of Hara Castle

Remains of Hara Castle

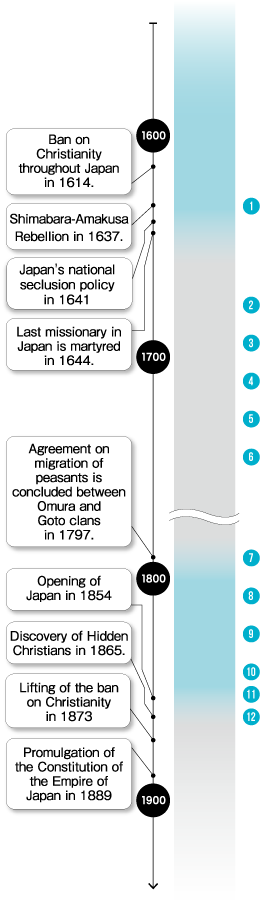

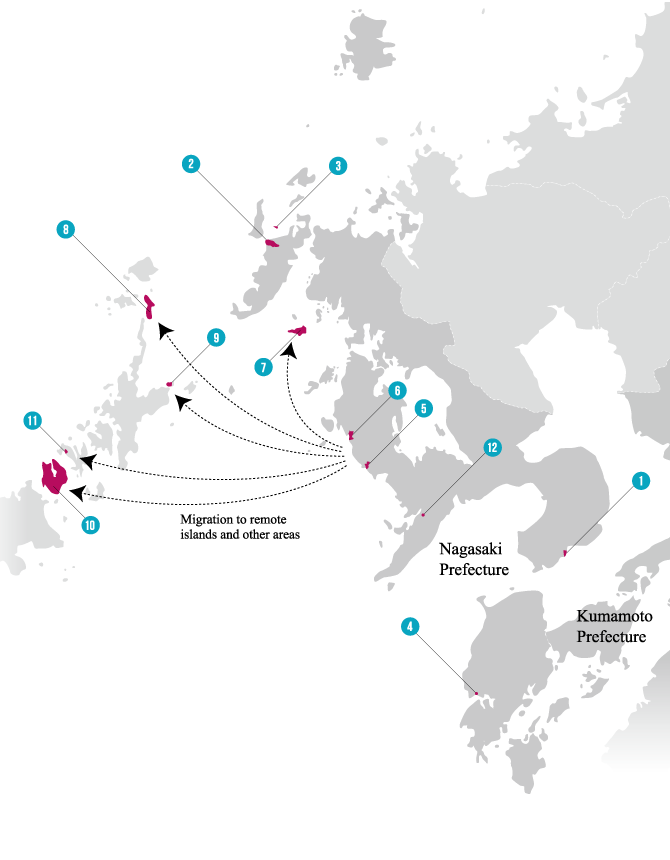

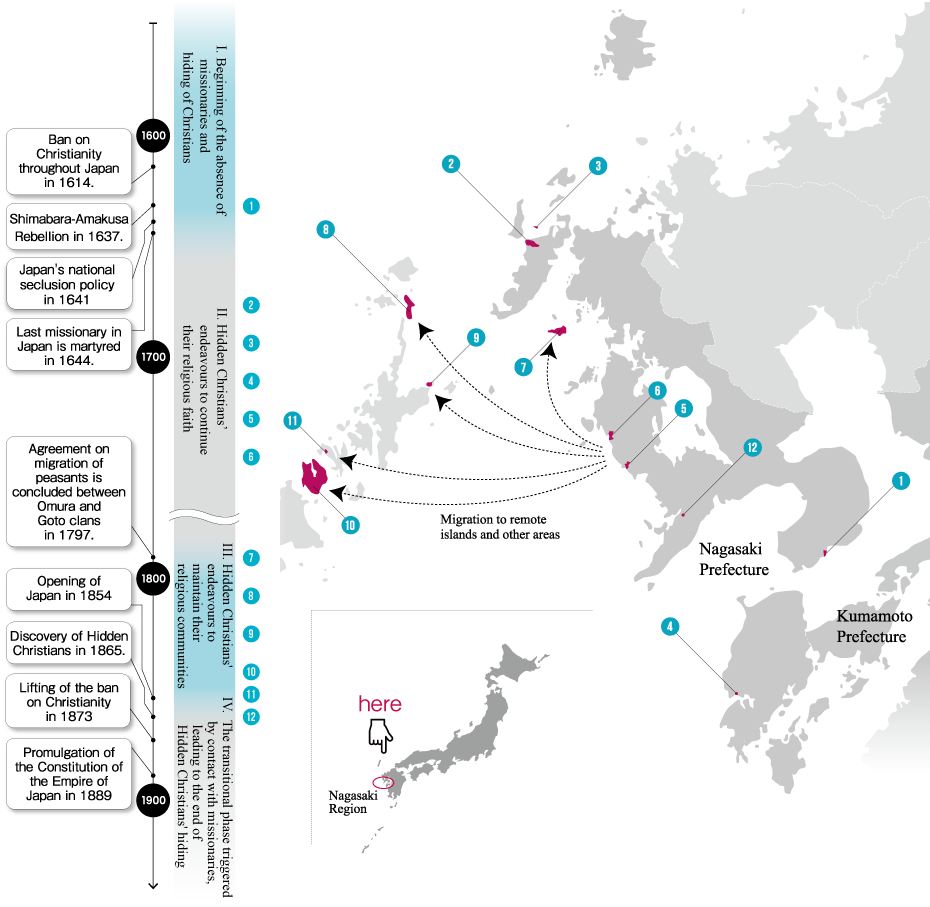

(Ⅰ) Origin of the tradition of continuing the Christian faith

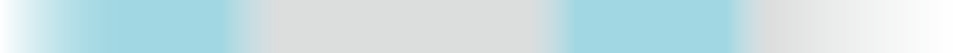

(Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

(Ⅱ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to continue their religious faith

(Ⅲ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to maintain their religious communities

(Ⅳ) The transitional phase triggered by contact with missionaries, leading to the end of Hidden Christians' hiding

(Ⅰ) Beginning of the absence of missionaries and hiding of Christians

(Ⅱ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to continue their religious faith

(Ⅲ) Hidden Christians' endeavours to maintain their religious communities

(Ⅳ) The transitional phase triggered by contact with missionaries, leading to the end of Hidden Christians' hiding

|

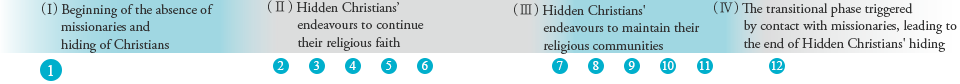

The site of the main battlefield during the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion, after which the remaining Christians had to go into hiding and find ways out to continue their religious faith by themselves. |

-

Animation Video (Remains of Hara Castle)

The Remains of Hara Castle is one of the components that bears testimony to what triggered the hiding of Japanese Christians. The castle remains became the major battlefield during the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion during the period when the ban on Christianity became stricter on a national scale. The rebellion had a great impact on the Tokugawa Shogunate and triggered the establishment of Japan’s national seclusion policy for over two centuries, prohibiting the arrival of Portuguese ships that could be used to smuggle missionaries into Japan. Under this seclusion policy and the subsequent absence of missionaries, the remaining Christians were left to maintain their faith in hiding by themselves, and they would have to find a new place to maintain their religious communities.

Basic information

| Designation title as cultural assets | Location | Designation category | Year of designation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remains of Hara Castle | Minamishimabara City, Nagasaki Prefecture | Historic Site designated by the national government | 1938 |

Access

>Hara Castle(”Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region” Information Centre)

※A new window opens.

Remains of Hara Castle

Remains of Hara Castle Kasuga Village and Sacred Places in Hirado

Kasuga Village and Sacred Places in Hirado Kasuga Village and Sacred Places in Hirado

Kasuga Village and Sacred Places in Hirado Sakitsu Village in Amakusa

Sakitsu Village in Amakusa Shitsu Village in Sotome

Shitsu Village in Sotome Ono Village in Sotome

Ono Village in Sotome Villages on Kuroshima Island

Villages on Kuroshima Island Remains of Villages on Nozaki Island

Remains of Villages on Nozaki Island Villages on Kashiragashima Island

Villages on Kashiragashima Island Villages on Hisaka Island

Villages on Hisaka Island Egami Village on Naru Island

Egami Village on Naru Island Oura Cathedral

Oura Cathedral